Protected Animal Species.

There are many protected species across the UK, and from time to time, residential surveyors may come across certain protected animal species whilst inspecting property. In this article, we have provided a roundup of the most likely protected animal species you may come across (or see signs of) during your inspection of residential property. We have broken each species down with information about the law, the signs they may be present, defects that could result from their presence, and what you should report to your client. It should also be noted that if you suspect or come across any protected species, you should not disturb the area and inform the homeowner or person in charge of the property of your findings and the implications of disturbing the species, as described in this article.

We are going to focus on:

- Bats

- Breeding birds

- Barn owls

- Badgers

- Great crested newts

We will also briefly touch on Dormice.

Bats

There are 18 species of bats in the UK and Ireland. Pipistrelle bats are the smallest weighing around 5 grams (less than a £1 coin). The largest is the Noctule with a wingspan of 33-45cm.

Bats are protected because bat population numbers have been declining and they play a significant role in terms of biodiversity. Some bats are ‘indicator species’ meaning changes to these bat populations can indicate changes in aspects of biodiversity. For example, bats might suffer when there are problems with insect populations as UK bats feed on insects, or when habitats are destroyed or poorly managed.

The Law

The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 is the primary legislation which protects animals, plants, and habitats in the UK by prohibiting and limiting actions involving wild animals. Prohibitions include taking, injuring, killing, and disturbing. It is also an offence to disturb places used for shelter and protection.

In Britain, all bat species and their roosts are legally protected by both domestic and international legislation. This means you may be committing a criminal offence if you:

- Deliberately take, injure, or kill a wild bat

- Intentionally or recklessly disturb a bat in its roost or deliberately disturb a group of bats

- Damage or destroy a place used by bats for breeding or resting (roosts), even if bats are not occupying the roost at the time

- Possess or advertise/sell/exchange a bat of a species found in the wild in the EU (dead or alive) or any part of a bat

- Intentionally or recklessly obstruct access to a bat roost

- Set and use articles capable of catching, injuring, or killing a bat (for example a trap or poison), or knowingly cause or permit such an action. This includes sticky traps intended for animals other than bats.

Breaking the law can incur significant fines of up to £5000 per incident or even per bat, up to six months in prison and forfeiting the equipment used to commit the crime. The penalty could be even greater for harming a large number of bats. Bats are a European Protected Species (EPS), so they receive full protection under The Conservation of Species and Habitats Regulations 2010.

Signs they may be present

There will be some tell-tale signs, even if the bats are not in residence.

Look for bat droppings on windows, walls, or sills. In the roof void droppings may be below the gable ends or in a line under the ridge. Bats may be visible on ridge beams inside the roof void but as they are very small they can easily tuck themselves away from sight.

Bat droppings are dark brown or black and vary between 4 and 8mm long. They look very similar to mouse droppings but the way to tell them apart is the ‘crumble test’. The Bat Conservation Trust suggests rolling a dropping in a piece of tissue between your finger and thumb and if it feels hard then it is probably mouse dropping. A bat dropping is small and dark and will crumble to dust when crushed because it consists of fragments of insect exoskeletons, the diet of UK bats.

Figure 1: Gable end wall in context with bat droppings on boarding

Figure 2: Close up of bat droppings on boarding

Figure 3: Bat droppings also on blockwork to gable end

Potential property defects

The main problem associated with the presence of bats is the severe limitation on the repair and development of a property and the fact that they interfere with the occupation of that property (for example, if you have bats in the loft, you cannot use the loft for storage or even enter the roof space).

However, very rarely, some buildings do have such a large number of bats that the bats themselves cause damage to the property. There is an interesting article on St Hilda’s church in Ellerburn, Ryedale that had a significant roost of bats. They caused considerable damage to some of the valuable artefacts in the church and even caused the parishioners to stop using the church for a period of time.

Large numbers of bats can also be associated with health problems in humans (this was reported in the St. Hilda’s case.) Histoplasmosis is a lung disease caused by the fungus associated with decaying bat faeces. In most cases, this is a very mild disease but may be more serious for people with underlying health problems.

Reporting to your client

You should report your findings in your survey for your client, explaining you suspect or identified that bats/a bat roost is present in the property and that it is illegal to disturb the roost. If they wish to use the loft for storage or are planning works that will disturb the roost, they will need to seek advice from a specialist.

Breeding birds

With more than 500 species of wild bird residing in the UK and around 200 species that breed here, it is important to understand the law and implications of breeding birds. Some birds, such as house sparrows and starlings, are declining in the UK partly as a result of the loss of nesting sites.

The Law

All wild bird species, their eggs and nests are protected by law under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. You’re breaking the law if you:

- intentionally kill, injure or take wild birds

- intentionally take, damage or destroy a wild bird’s nest while it’s being used or built

- intentionally take or destroy a wild bird’s egg

- possess, control or transport live or dead wild birds, or parts of them, or their eggs

- sell wild birds or put them on display for sale

- use prohibited methods to kill or take wild birds

Penalties that can be imposed for criminal offences in respect of a single bird, nest or egg contrary to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 is an unlimited fine, up to six months’ imprisonment, or both.

Signs they may be present

Birds breed between February to August, so be aware of their presence during this time. Birds can nest in gutters, eaves, and the roof itself. You may spot birds disappearing into the eaves when inspecting the property outside. If you have access to the roof space, look out for any physical evidence of birds nesting such as nesting material and bird faeces, and listen out too as you may hear any baby birds.

It may also be a good idea to ask the current owner or tenant if they hear any birds in the morning coming from the eaves area.

Figure 4: Starlings appearing from eaves of roof

Potential property defects

If birds are nesting in the eaves, it is more likely to result in blocked gutters where birds are taking nesting materials in.

Reporting to your client

If you identify breeding birds during your inspection, you can report this in your survey and advise the client of the implications of disturbing nests or killing or injuring breeding birds. It would be prudent to explain that activities such as trimming or cutting trees, bushes, hedges and vegetation can affect wild birds, particularly during the breeding season. They should also be aware of breeding birds if planning on renovating, converting, or demolishing a building.

Barn owls

There are 5 species of owl in the UK, but barn owl numbers have decreased since the 20th century by as much as 70% between 1932 and 1985, according to the Barn Owl Trust. These declines are largely the result of improvements in the way farmers cultivate their land.

Figure 5: Barn owl

The Law

Barn owls have extra legal protection. For these bird species, in addition to the list in breeding birds above, it’s also an offence to do the following, either intentionally or by not taking enough care:

- disturb them while they’re nesting, building a nest, in or near a nest that contains their young

- disturb their dependent young

You could get an unlimited fine and up to 6 months in prison for each offence if you’re found guilty.

Signs they may be present

As their name suggests, you may come across barn owls in barn buildings or outbuildings that aren’t disturbed often, as well as tree hollows. Some properties may even have owl nest boxes built especially for breeding barn owls. Although rare, they have been known to nest in chimneys and roof structures.

Figure 6: External view of barn owl nesting box built into roof structure. Copyright: The Barn Owl Trust https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/

Figure 7: Internal access of the barn owl nesting box. Copyright: The Barn Owl Trust

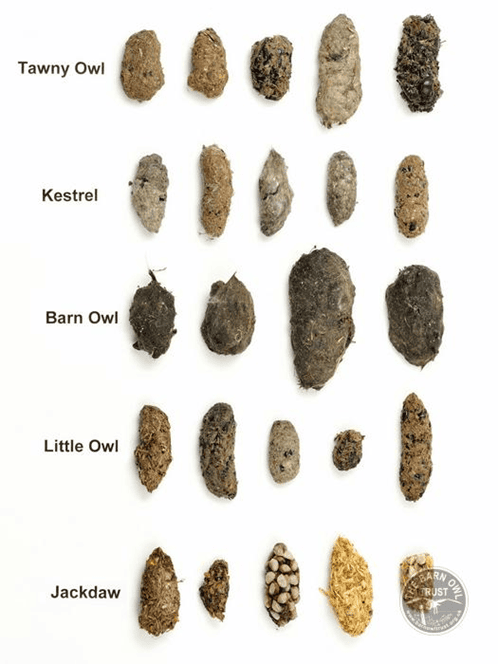

Look for signs of ‘pellets’; these are regurgitated pellets of food the owl could not digest such as hair and bone.

Figure 8: The different pellets regurgitated by different bird species. Copyright: The Barn Owl Trust

Owl droppings are usually white and watery (but can be black or black and white). The Barn Owl Trust has a useful page on signs of occupation here: https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/barn-owl-facts/signs-barn-owl-occupation/

Figure 9: Pellets and owl faeces present in this loft space, as well as a hole that has been cut in the gable end for access to the loft. Copyright: The Barn Owl Trust

Potential property defects

Generally, owls will not damage property, but of course, if they have been nesting in a roof, they will leave roosting debris, faeces, and possibly dead rodents.

Barn owls only need a gap of 7cm x 7cm to gain access, therefore, poorly maintained buildings may allow them access into roof voids etc. Be aware of this if inspecting property that is in a dilapidated condition. If you do find signs of Barn Owls in a roof void, it would suggest there are gaps in the building that may not be visible to you on your inspection.

Reporting to your client

If you suspect barn owls are present, you should report this to your client as well as notify your client about the law around barn owls and disturbing them.

Badgers

Badgers live in underground ‘setts’ (tunnels and chambers) in mixed-sex groups of four to eight, and they can grow up to 1 metre in size.

Figure 10: Badger in woodland

Although not endangered (there are an estimated 485,000 badgers in the UK), badgers are a protected species because of illegal badger baiting, a blood sport in which badgers are baited with dogs.

The Law

Badgers and their setts are protected by law under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992. It is an offence to:

- Wilfully kill, injure, or take a badger (or attempt to do so)

- Cruelly ill-treat a badger

- Dig for a badger

- Intentionally or recklessly damage or destroy a badger sett, or obstruct access to it

- Cause a dog to enter a badger sett

- Disturb a badger when it is occupying a sett

If found guilty, offenders may be subject to fines or even custodial sentences.

Licences from Natural England may be granted to close down setts, or parts of setts, prior to development or to permit activities close to a badger sett that might result in a disturbance. A licence will be required if a sett is likely to be damaged or destroyed in the course of development or if the badger(s) occupying the sett will be disturbed.

Reporting to your client

Badger setts can extend to more than 50 metres and it is illegal to damage or destroy them. If present, homeowners may face some issues if they want to carry out works. You should report that you suspect badgers and provide information on the law relating to badgers.

Great crested newts Triurus cristatus

There are only three types of newt in the UK and the Great Crested Newt is the biggest and rarest. They can grow up to 17cm and have black or dark brown skin that is granular in appearance. They have a unique orange or yellow underbelly with dark spots. The males will develop their ‘crest’ in spring (at the beginning of the mating season). They spend the majority of life on land, and they migrate to ponds during spring when the mating season begins.

Figure 11: Male great crested newt (Source: Natural England)

Great nested newt eggs can be identified by a jelly capsule around 4.5 – 6mm long, with a light yellowish centre; they are usually deposited on leaves.

The Law

It is estimated that there are about 75,000 populations in the UK. A reduction in the water table, in-filling for development, agricultural intensification and the subsequent neglect of ponds and the stocking of ponds with fish has caused a reduction in the number of ponds suitable for breeding. In England and Wales, the great crested newt is protected under Schedule 2 of the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 and under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended).

It is an offence, with certain exceptions, to:

- Intentionally or deliberately capture, kill, or injure GCN;

- Intentionally or recklessly damage, destroy, and disturb GCN in a place used for shelter or protection, or obstruct access to such areas;

- Damage or destroy a GCN breeding site or resting place;

- Possess a GCN, or any part of it, unless acquired lawfully; and

- Sell, barter, exchange, transport, or offer for sale GCN or parts of them.

The penalty for committing an offence can be an unlimited fine. There was a case several years back where a civil engineering company was fined £50,000 for illegally dumping construction waste into a great crested newt habitat (read more here).

Signs they may be present

The great crested newt may be found over all of England, Wales and Scotland but need suitable ponds surrounded by good quality ground habitat if they are to thrive. They do not breed in small garden ponds but prefer middle-sized ponds (which can be artificial) and prefer semi-natural grassland and woodland for foraging etc. Therefore, you are unlikely to come across great crested newts in small urban gardens, but you might find them in larger, more rambling ‘less tidy’ locations.

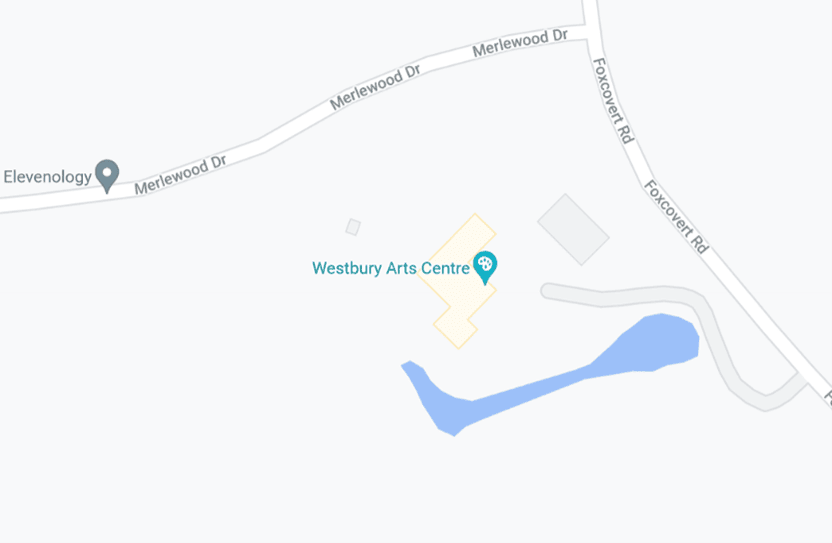

Westbury Arts Centre in Milton Keynes, housed in a former farmhouse, has a known colony of great crested newts. The property is still in a semi-rural location, has the remnants of an old moat (seen more clearly on the map rather than the aerial photograph) and has a now disused swimming pool on site. While the gardens are managed, they are not pristine, providing ideal ground conditions for the newts.

Figure 12: Satellite view of Westbury Arts Centre

Figure 13: Map view of Westbury Arts Centre

Reporting to your client

If great crested newts are present, then they could be affected by the following work:

- Maintenance works to ponds, woodland, scrub or rough grassland.

- Removing dense, scrub vegetation and ground disturbance.

- Removing materials, such as dead woodpiles.

- Ground excavation works (including repairs to foundations).

- Filling in or destroying ponds or other water bodies.

If there is a possibility that great crested newts could be affected by any sort of development or maintenance work, surveys by an ecologist may be necessary and it is possible that a licence from Natural England would be needed before any work could commence.

It would usually be necessary to do this if:

- There are historical records of newts within the land or close to the land proposed for development (this might be verbal records. The presence of newts at Westbury is not documented but is known about by the local authority)

- There is a waterbody within 500m of the application site boundary.

If you identify or suspect the presence of great crested newts, you should report this to your client and make them aware of the law around great crested newts.

Dormice

There are six species of mice in the UK. There are five native species, including the native dormouse—also called the Hazel Dormouse or Common Dormouse (Latin name Muscardinus avellanarius)—but the sixth— the Edible Dormouse (Latin name Glis glis)—was introduced into a private collection in Hertfordshire in the early 1900s and subsequent individuals escaped into the wild and, there is now an estimated 10,000 of this species happily living in the wild. There is some confusion about the status of the two species of dormouse.

The Law

The number of native Common or Hazel dormice have declined dramatically over the last century and continue to do so today. This is primarily due to the loss and fragmentation of woodland habitat as a result of forestry, urbanisation and agricultural practices. These native dormice are fully protected and an endangered species under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, as amended.

The Hazel dormouse is a rural dwelling animal, but the Edible dormouse will happily make itself at home alongside humans in loft spaces or cupboards, and several house fires have been attributed to damage to electric cables caused by them.

Although protected under the Bern Convention, it is now permissible to trap edible dormice under licence from Natural England for “ the purposes of preserving public health and public safety, and to prevent serious damage to crops, fruit, growing timber and other forms of property”. (Read more here.)

Their cousin, the Edible dormouse—so-called because they were an edible delicacy in ancient Rome—is now classed as a non-native invasive species as it is not native to the UK. It is much bigger than the hazel dormouse being more ‘squirrel like’ in appearance.

The Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, also known as (the Bern or Berne Convention), is a binding international legal instrument covering natural heritage in Europe and some African countries. The family Gliridae to which both species of dormouse belong is covered by the Bern Convention.

Bat Case Study 1

St Hilda’s Church in Ellerburn near Pickering was closed for several months in 2011 due to a colony of Natterer’s bats which had been living in the church for ten years and eventually took over. This was a very large roost and eventually, it drove the congregation away from the church which had to hold services outside.

According to the churchwarden, the walls, floors and altar of the historic Saxon church were covered with bat droppings and sprayed with bat urine damaging the woodwork, church artefacts, stone flooring slabs, pews, choir stalls, pulpit and font. Some of the volunteers at the church became ill due to the large volume of droppings and urine present.

Eventually, the church was granted a licence from Natural England to block up some of the access points which the bats have been using to colonise the church. They could continue to live in the roof of the church, but not in the church itself. The clean-up operation was claimed to have cost thousands of pounds and took a specialist team of five people two days to complete and gather 13kg of bat droppings!

Bat Case Study 2

Westbury Arts Centre in Milton Keynes is known for both its bat and great crested newt populations.

Within the curtilage of the site is an old barn which is used during the warmer months. However, the barn roof and part of the gable wall were damaged in storm Dennis in early 2020.

Because of the known bat population, before essential repairs to the barn roof and gable end could be carried out, the Arts Centre had to commission a bat survey, necessitating the attendance at site on three separate occasions.

Then, the presence of bats was noted around the barn with evidence of bat droppings in the barn and a licensed ecologist was on site for the duration of the repairs. The additional costs on top of the essential repairs were in the order of £1500.

List of useful resources

Bats Conservation Trust: https://www.bats.org.uk/about-bats

The Barn Owl Trust: https://www.barnowltrust.org.uk/

The Badger Trust: https://www.badgertrust.org.uk/badgers

Great Crested Newt Conservation Handbook: https://www.froglife.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/GCN-Conservation-Handbook_compressed.pdf

The Wildlife Trusts: https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/